Borders, bridges, brackish spaces

Liminal no-man’s land: where NJ Transit Corporation and the Metro-North Commuter Railroad Company dba: MTA Metro-North Railroad, a New York public benefit corporation, meet near the middle at their shared New York-New Jersey border to provide commuter rail service somewhere between partnership and truce.

There is a train station along the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) Metro-North Port Jervis Line in Suffern, New York, in the Lower West Hudson Valley, that is 500 yards north of the New York/New Jersey border.

It’s a New York station, owned and operated by New Jersey.

Below the border the Port Jervis line becomes either NJ Transit’s Main or Bergen County Line—not by transfer or merger, and often in name only.

They ride the same tracks, often seamless routes, operated by a New Jersey state agency, partially in New York, through an operating agreement that splits facility and service obligations.

Identical Comet V cab cars, one with MTA branding, the other with NJ Transit branding, depart from Suffern for Hoboken minutes apart.

Without a map or signage, there’s no real telling between where Suffern, NY ends and Mahwah, NJ, Suffern’s slightly southern neighbor, begins, in mid-subdivision.

The MTA sets and receives fares from Metro-North stations, reimbursing NJ Transit for operating costs. Both systems collaborate on scheduling. They share some equipment.

Maintenance for Metro-North stations is assigned to the MTA, train operations to NJ Transit, except in Suffern. NJ Transit operates both trains and station in Suffern, NY.

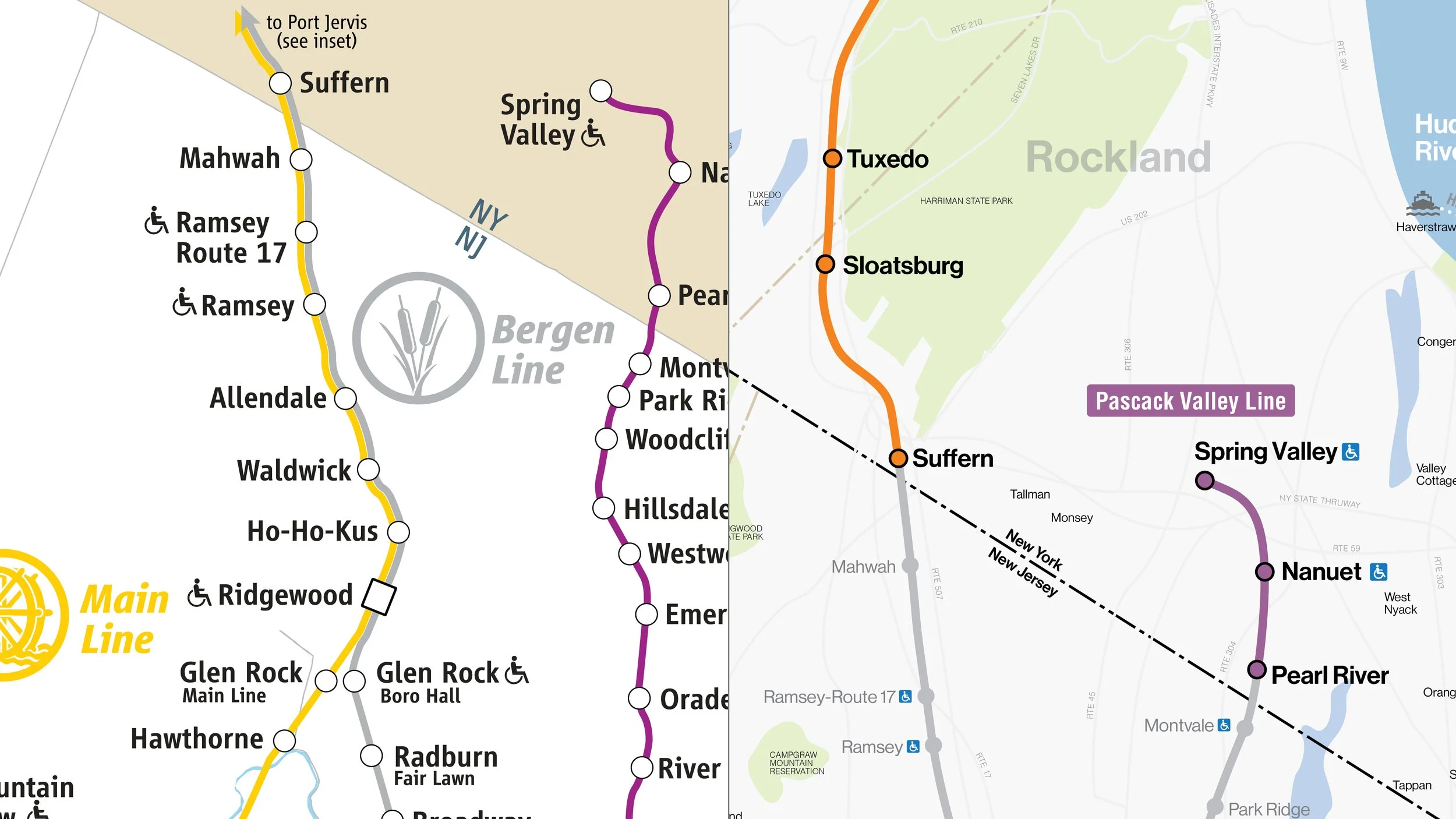

NJ Transit and MTA call the same rail service by different names. They have separate brochures (NJ Transit’s vs. MTA’s) and system maps, each featuring the same information, organized and illustrated differently.

Different representations of the same route on NJ Transit’s system map, left, and MTA’s Metro-North system map, right. Metro-North’s system map appears on the reverse of the New York City Subway map.

One way you can tell you’re riding the Metro-North? Station signage: in New York, station names are displayed Helvetica Bold Italic, black letters on a white background. New Jersey stations are just the opposite: Helvetica bold, white letters on black background.

These minor differences signal more complex and consequential organizational rifts.

Even in harmonious times, the relationship is delicate.

Metro-North-branded street signage points to Suffern Station, where Metro-North riders purchase their tickets from an NJ Transit kiosk.

There are 9 stops along the Port Jervis line in New York, before the New Jersey leg of the trip becomes the Main (15 stops) or Bergen (14 stops) Line, at times splitting to collect and shuttle commuters on both sides of the Passaic River toward or from New York.

A second line, the Pascack Valley Line, has 3 stops in New York and 14 stops in New Jersey (it is referred to by New York and New Jersey state agencies by the same name: same routes, same schedule…)

These are not favored lines by either system, more obligatory—the Metro-Rail overall sees roughly 60,000,000 annual rides. Only 1,000,000 of those are on the two lines west of the Hudson. Overall, the Metro-North operates 700 trains each weekday, with NJ Transit operating 64 daily trains on Metro-North’s behalf.

The current operating arrangement between the New York and New Jersey state entities dates to 1985, after NJ Transit took over passenger rail operations from Conrail, the conglomerate initially established by federal legislation and federally funded to subsume viable rail lines from bankrupt commuter railroads. Conrail commuter service disbanded early-Reagan, with the federal government selling its controlling interests and states taking over commuter service.

A 1996 agreement was replaced the 1985 agreement, which was amended periodically through 2006, when a revised version codifying amendments was established to supersede previous agreements. The contract, established through 2012, auto-renews annually per a continuation clause. The routes themselves have seen minimal modification.

Who else is involved—primary groups.

Post-Conrail dissolution, the tri-state area and northeast corridor remain a complex tangle of interconnected systems with shared service interests and goals, tangent or distinct governing bodies, and disagreements and conflicting obligations over how best to accomplish those shared goals.

A critical example: MTA pays its Metro-North engineers better then NJ Transit pays their counterparts west of the Hudson. NJ Transit engineers are paid less to operate Metro-North trains then Metro-North engineers. Pay inequality is valid grounds for resentment.

In the past, the MTA has lured engineers from NJ Transit with higher pay. During one period in 2019, overstaffing in preparation for a mass retirement event, averaging one monthly poaching, led to a surplus east of the Hudson, and a shortfall to the west.

Signs welcome passengers to New York and to Suffern; the NJ Transit Suffern Station.

The imbalance created untenable conflicts of interest: with fewer NJ Transit engineers, the quality of combined Metro-North/NJ Transit service decayed to such levels that, with train cancellations and late arrivals, that Metro-North withheld fare hikes assigned to all other stations as a tacit apology—while MTA paid out salary and benefits to engineers to stay home.

MTA and NJ Transit engineers belong to different unions: MTA engineers to the Association of Commuter Rail Employees (ACRE)–based in New York, and NJ Transit engineers to the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers and Trainmen (BLET), based in Michigan. An MTA proposal for their own engineers to man Metro-North trains west of the Hudson temporarily to fill in staffing gaps was blocked by ACRE, claiming junior engineers would be cherrypicked for cost-savings, and set soft precedent for future salary range negotiations.

Metro-North engineers who had been NJ Transit engineers and operated Metro-North lines as NJ Transit engineers, were blocked from operating Metro-North trains as Metro-North engineers—with New York and New Jersey commuters along these lines suffering the same.

MTA ridership of the NJ Transit/Metro-North combined lines is comparatively small—a few thousand daily riders, meaning Metro-North riders have a comparatively smaller voice when concerns over trains and service arise.

NJ Transit has primary authority over operations, with MTA having limited governance in creating or enforcing policies. Contracted as the operator of the system, NJ Transit is the primary authority. MTA is seated somewhere between sideline and sidecar.