Traffic Studies; Field Notes

For 2 months and 1 week in early 2023, I worked as a transportation planner in Orlando. I couldn’t understand how co-workers could consult on routes and systems they hadn’t ridden.

STOP.

The Clermont Park & Ride is 2.5 acres of 139 parking spaces just south of a Wawa along Route 27. I have never seen more than 7 cars parked here.

It is a 5-mile, or 11-minute ride from my driveway to the Park & Ride. From here, the LakeXpress Route 50, named for the State Road 50 it traverses, reaches Mascotte to the west and Winter Garden to the east, with a transfer via the Lynx 105 to Downtown Orlando.

The drive from this location to Downtown Orlando is 36 minutes. By bus, it is no fewer than 131 minutes, including a curbside transfer at a stop with no shelter or shade. I wonder how many transportation experts agreed this many people would drive their cars to the bus.

There are 2 old oak trees near the rear fence that have been cornered and paved in. They provide the only available shade, 9 bus lengths from the boarding area. Two benches are placed at the base of one tree, shaped like macaroni so no one will sleep on them. A city cop takes advantage of one of the few shaded spaces, eating his lunch with the engine running. I dodge the sun, sit down, stand up, kick rocks. I move my car 3 times around unclear signage. I wait, idle, wasting time and gas.

The final stop east is at Winter Garden Regional Shopping Center, closest to the intersection of S Park Ave. and perpendicular to the entrance of an Aldi, the anchor store in the shopping center.

For me, today and all week, my trip ends here.

STOP.

The driver’s cockpit seat is behind bank teller glass. She is not to be robbed, stabbed, or spit on. She has crunchy, silver-grey curls with a few stubborn splotches of brown box dye, and wears the coarse blue cotton work shirt of a mechanic or facilities staff, two-tone emergency vest, dark navy Dickies, and tan gas station sunglasses. The soles of her work boots are tall enough to walk safely across railroad spikes.

I move to a back seat. Sharply ergonomic, it pinches in my lower back. The chattering blue plastic is built to repel spills and urine. The low hum of the bus, the warble of the gears, the pull and jerk, roll over waterbed shocks.

The first rider on my bus boards at a stop across the street from a Mexican restaurant. She wears the gum-soled non-slip sneakers common in restaurants, and smells like a long shift in a hot kitchen. She wears mostly black: leggings, shirt, socks, with a dark asphalt hooded sweatshirt. Her hair has been bleached and now stained copper, pulled in a bun that is coming loose. She speaks in quiet Spanish to her phone for less than a minute, then takes a deep, shaking breath as she decompresses and shrinks. Her non-slip shoes hold onto the floor, her glasses to her face, as she rubs her eyes.

A woman with light skin with clumpy, thinning hair gets on at the stop beside a Publix parking lot. Her chin falls. She’s disappointed in something and weary. She wears a black sweater, the green collar of her work shirt visible above the neckline. She summits the steps, sets her feet, looks upwards, shudders, and welcomes a deep, triumphant breath. She relaxes into her cupped seat, conceding a restrained smile.

She’s carrying a small patent leather backpack that could be hers or her granddaughters. It is patterned with embossed flower shapes.

One by one, riders get on, some get off. We pass hidden lakes, hidden mansions, dead trees, backyard greenhouses, a bus depot, oaks, palms, gas stations, oval grass patches, square buildings, shadows, trucks, signage, shade, parks, pre-historic lots for sale…

STOP.

A woman with thick and wavy white hair frantically scratches for an itch on her scalp using the tip of one temple of her wireframe glasses.

A slight man, bald and birdish, wears dark khakis and thin buttoned-up pinstripes. He hunches forward in his seat, gripping his phone at an angle to his face to push the phone’s speaker through his ear, turning the screen backwards. He’s straining to listen to two fresh-faced, bubblegum influencers dramatically narrate a crowdless political rally held in a high school gymnasium.

I can’t look away as he listens. Together we form a complete audience.

Opposite this slight man sits a gentleman who could be a chef or sell mobile phones. He has reckless white hair slicked back into salted corduroy. He wears all black: watches his black phone through black sunglasses, wears a dark beaded necklace over a black, deep V-neck t-shirt; black watch, black belt, black pants, black socks, polished black chukkas.

As he stands at his transfer stop, eyes hovering over his phone and distracted, he reaches across his body to grab for his black travel bag. With this twisting motion his black belt betrays him, pulling low on his waist to expose shockingly pink underwear. He freezes in a middle school nightmare.

Dropping the bag, he grabs his belt and sits back into his pants, eyes low and aware for any potential witnesses. I stare holes in the floor as he glances past. With the bus stopped, he gathers his items and, eyes forward, skitters off.

STOP.

A young girl boards the bus, short, tan, and punky. She wears teal headphones with cat ears molded into the headband, sitting upright and absorbing her phone.

One rider makes use of the bike rack on the front of the bus. She wears all black scrubs, a black cloth mask, dark round glasses, and a short bob that hides the details of her face. Gold glitter accents her shoes, and she carries a thick black leather fanny pack, polished by wear to a blue patina, like a messenger bag. I can’t tell if she is coming or going.

STOP.

The Winter Garden Regional Shopping Center transfer stop is marked by a bench that is a billboard for Craig Martin, insurance agent. It features his actual-size headshot. I wonder how many riders have purchased his insurance products, and how many sit across his face each day, on average. His eyes, bleached grey from the exposure, remain unblinking, stoic, hostage.

A pedestrian shortcut has formed through the customer pick-up area in the shade of the short outside wall of the bustling Aldi. Customers and cars mix with pedestrians passing through on foot and by bike as they spin and weave in something like choreographed chaos.

“Share the road! You’re lucky I’m not a cop! I’d make a good one!” a woman you would call ma’am yells at a dark SUV that has cut her off entering the pedestrian shortcut. She wears a black felt derby hat low on her eyes and covered with dozens of colorful enamel pins. Her long dress is Bealls signature, watercolor flowers. She pedals in chunky black sandals on a curvy one-speed beach cruiser, keeping pace with the offending SUV. A milk crate is fastened to her handlebars. She chases the SUV from the parking lot, then returns to grocery shop, pulling reusable bags from her milk crate.

A man with dripping red curls and skin like damp newspaper wears light grey sweatpants and a white t-shirt that has been bleached yellow. He walks with shoulders slumped, looks right, then left, then right.

He jaywalks.

STOP.

Past this shortcut, on the opposite side of S Park Ave., Magic Johnson flashes two thumbs up for low-cost health insurance on the backrest of a droopy wooden bench. The bench marks a bus stop and looks like an album cover—curbside with no sidewalk or context, detached from any logical path, it sits nowhere.

It’s an interesting choice, putting an all-star on the bench.

To my left, a long row of flimsy, blunted iron spears surround 12 terra cotta and tan duplexes. A drainage ditch within the spear fence would be a moat in a hurricane.

The duplexes look out at an RV campground the width of 6 city blocks* that is wrapped in the same fencing. I wonder what sort of rivalry is simmering. Just beyond the campground, at a frantic intersection, signage marks the threshold beyond which no golf carts may pass.

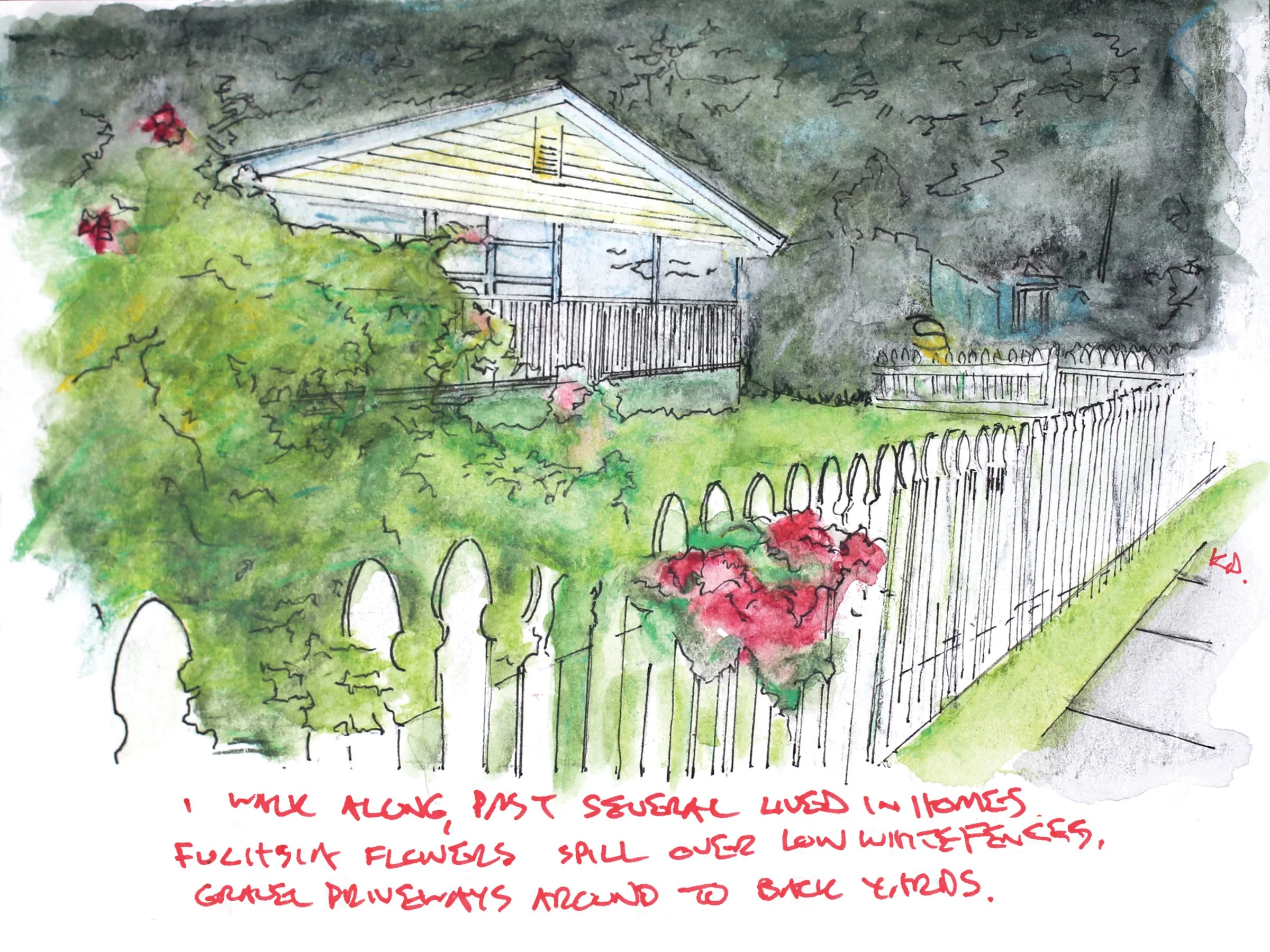

The honey marshmallow of a distant cigarillo, unmolested, perfumes my sidewalk. I startle at a whisper over my shoulder, stale oak leaves blown under a Hyundai. Many more cars pass. I walk along the sidewalk, past several lived-in homes. Spanish moss swings from old oaks providing intermittent shade. Mature roots have pushed slabs of sidewalk concrete up on angles. Red and yellow hibiscus push into fences. Fuchsia flowers of bougainvillea spill over and push past these fences.

A man with a barnacled beard in a maroon sleeveless tee reading “Jesus” in all-caps coasts past on an electric bike, greeting me as he approaches:

“What’s up hoss.”

Other bikers pass giving nods and hellos.

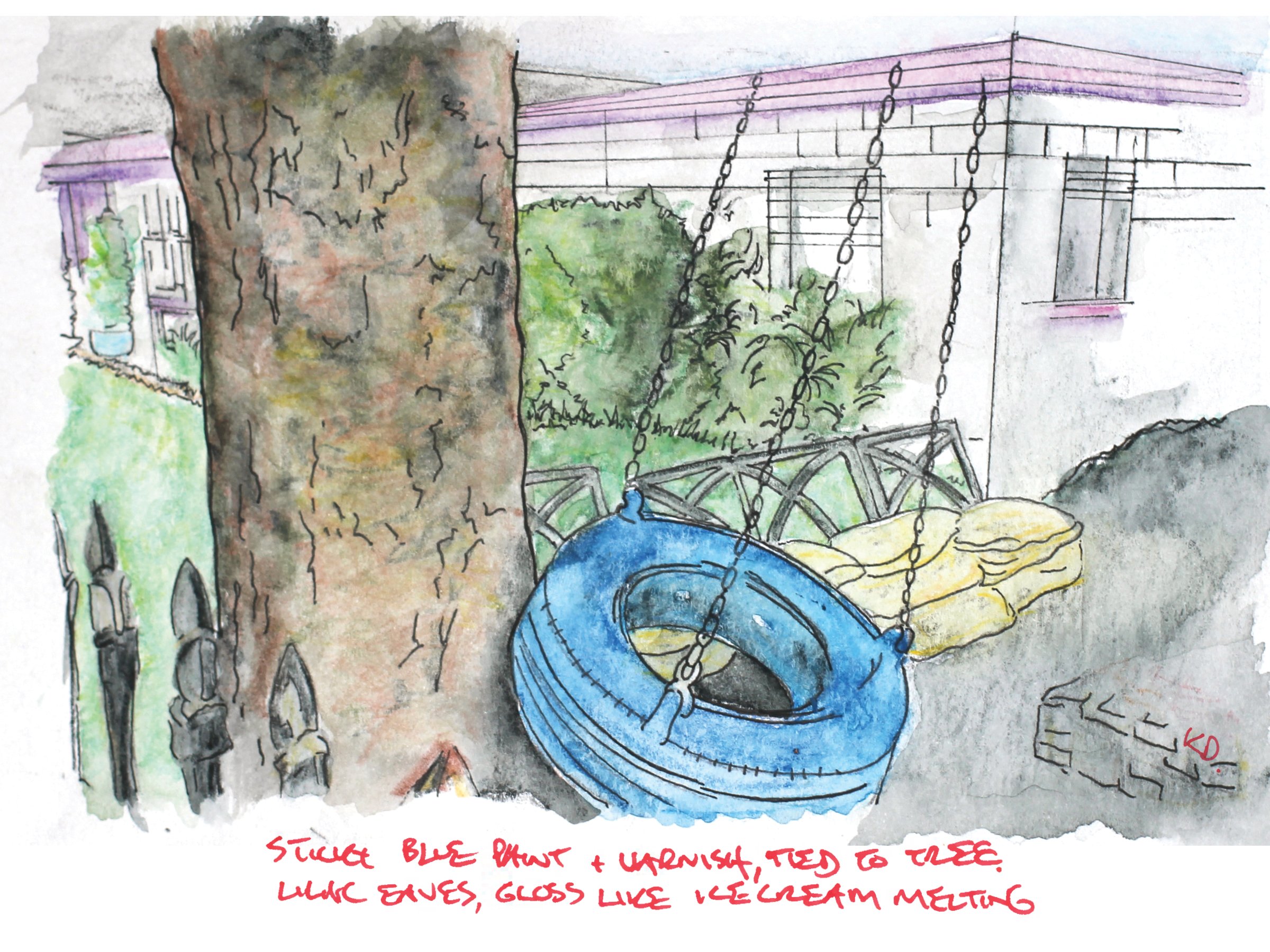

I pause on the sidewalk, noticing a waist-high chain link fence that has been painted Easter yellow. Barbed wire is wrapped around the cross bar of the entrance gate, also painted Easter yellow. It’s a fence to be careful opening or walking near. A tire slathered in sticky blue paint and varnish is tied to a tree and leans over a short fence that walls in a driveway as a garage. One house still is decorated for Christmas with hung wreaths and rosaries. There are cars on lawns, overflowing car ports, gravel driveways that lead around back.

A low, white-walled church has a high black fence surrounding the campus, save for the front entrance, which is guarded by stained and buried wooden beams. There is no chain link mesh between these beams. A banner hung from the fence advertising a recurring fundraising event boasts, “You Name It ….. We Jerk It.” I wonder if anyone advised against this tagline.

On the church campus, behind church proper, is a cinder block home with chalky white walls and lilac eaves, with a gloss like melting ice cream. A pre-Covid Buick is parked under the car port, and leather sandals are left on the doormat.

I pass the Park of S Park Ave, several freshly drug baseball fields, and a modest monument to lost military.

Two tiny, yiping puppies, German Shepherds or Chihuahuas, are tethered at the front edge of one house. A stack of shipping palettes bends and slips into old mud behind a tree. A garden bench shares landscaping with an orange molded chair from a second or third grade classroom, behind a short white fence that is more decoration than boundary.

The next day I see a family of three posed on the garden bench and classroom chair eating Firecracker popsicles. A girl wearing a McDonalds’s uniform carrying a grocery bag from Aldi stops to chat. She is not immediate family but seems to know them well enough, as they share an easy conversation over the short fence.

A man on a bike stands on his pedals, pumping heavily and building speed before coasting into his seat like a bobsledder. He is wearing an Orlando Magic snapback hat backwards. Ahead a few hundred feet, he slips behind a fence in view of Magic Johnson, reappearing a few moments later to ride back towards me, slow and wobbly with sloppy eyes and a wet smile. He nods as he rides past, knowing me and Magic won’t talk.

STOP.

Talking past Craig Martin, a man in a fruit punch polo asks me if the next bus is headed to Mascotte.

“It is”.

From this stop, all next buses are headed to Mascotte. Satisfied with my answer, he retreats to what shade is available under a short Crepe Myrtle between the sidewalk and the parking lot. I see him there the next 3 days. It’s his stop. He was not asking for directions. It was an interview.

Seated against Craig Martin, she fumbles the transfer of an appliance from a black plastic shopping bag to a Navy backpack. The mouth of the backpack is not wide enough to accommodate the appliance, and she shifts it back to the plastic bag. What I had thought was a coffee maker is an electric can opener. I wonder if it was on sale or if she needs help to preserve her withering grasp.

She is tired, in her 60s, thin, frail. Her spotted skin is table linen hanging from broom sticks, her hair moppish and coarse. She evaluates the cover of a crisp white bus schedule she holds between her thumb and forefinger. Sensing I’m anxious, she looks up, running her tongue along phantom teeth. Her voice is cigarettes.

“It’s running late. It was supposed to be here half an hour ago. It’s on the other side of the road right now.” She points, controlling traffic.

“He likes to roll through stops when no one’s there and he’s running late. I call it a California Roll.” She knows the driver by his habits. “He should make the next light. He’ll be here in a couple minutes.”

I sit down to share the bench. The breeze is brackish, gently sweet from the crepe myrtle, harsh and hot from tires and grey exhaust.

“It’s the turnpike. The new extension making everything late. It’s not near here, but it’s putting a lot more people on the dang road.”

She knows the Route 50. She rides it to work in both directions: twice each week east for 2 shifts at B—** in Winter Garden, and 6 times each week west where she works something like full-time at Walmart. Most weeks, she works both jobs on different shifts at least once. From the back brace she wears, Velcro and pulleys from waist to chest, I’m sure she should not be carrying whatever weight she is carrying.

“Go ahead, fire me” she growls, daring the passing cars, proxy for management or any of her bullies. She’s fantasized about this confrontation probably her whole life.

She teaches me the way to save a dollar taking advantage of the transfer exchange between the 50 and the 105 by crossing the street; and that anyone who can last 90 days at Walmart receives a 10% discount for life. Our forearms share a matching sheen of summer sweat.

STOP.

As we get on the bus, she sits in the front, closer to the driver. I can sense she’s a bit hurt that I cut our conversation short and walk past her to the back of the bus. I feel guilty, and a little alone for her.

As I arrive the next day, she is sitting with Craig Martin. She looks up to see it’s me walking and shifts her eyes down, back to the cover of her schedule. I attempt a hello she is not interested in, then also look down, pulling away. She has forgotten me or is ignoring me.

After a silence long enough to have made her point, without looking up, she fills me in: “the bus is on time today.” I don’t know how she knows, but I’m grateful to join her on this ride at the front of the bus. I think about offering her a ride home. The idea fades.

The driver’s phone interrupts the humming gears, “O-oho, give me the beat, boys, and”…reacting deftly, she thumbs the phone silent in her pocket, never breaking gaze with the road.

A sinewy man in clawed jeans that are several shades of blue and a gray Nike athletic tee is the only rider in a group of 5 boarding the bus at once who is not outfitted in all black. He wears a thin zip-up hooded shirt, hood up, over a spandex wave cap. Several stops later, as he gets off, I catch the graphic on the back of this shirt: The New York Times Cooking. The New York Times masthead is in white, with Cooking in dense, bold orange block lettering.

He boards the bus again the following day, alone this time, arriving in the thick, piney air of charred herbs.

He is baked.

STOP.

Cooper Memorial Library is a satellite campus of Lake-Sumter State College. Two students board from the stop across the street. On an empty bus, they huddle together. One wears a medical mask and a tank top of cartoonish flowers. The other has blushing straw hair and wears the shirt of a restaurant along the route.

The girl wearing the mask bows in her seat to pull her mask low, palming a vape pen to her lips and blowing candy smoke to her scuffed Converse.

One man, ropey, enters wearing periwinkle socks stretched to the knee with Adidas track pants over them pulled to mid-shin; red Nike slides with a Calvin Klein hoodie with branded piping from wrist to hood. He’s carrying a custodian’s trash bag like carnival winnings. As he sits, he shifts though hidden items, leaving the mouth of the bag to hang low between his forearms, obscuring the contents of the bag. He rolls the top down, like sealing a sandwich bag, then props the bag against the window as a pillow, reclining sideways. He gives up on the nap in a few seconds, sits up, slides his feet into the aisle, pulls them back in, crosses his ankles, and clasps his hands as if in prayer, rotating his thumbs. Something is on his mind that is exhausting him and won’t let him sleep.

He twists up in his seat, holding the bag again, in discrete review of its contents. One item he needs to see in the light. He holds up a faded peach-colored baby onesie with blue stitching and trim. From its soft round edges and with this hint, the bag is full of clothes.

STOP.

Prehistoric lots for sale, parks, shade, signage, trucks, shadows, square buildings, oval grass patches, gas stations, palms, oaks, a bus depot, backyard green houses, dead trees, hidden mansions, hidden lakes…

All week, an awkward man sits in the back of the bus. Dark hair, errant and greasy. His dark shirts dusted in beard dander. Sneakers, shorts. Sometimes a hat. He looks up, whispers to himself, giggles here and there, stares ahead then out the window, takes notes in red felt marker in small journals, or sometimes on the printed maps and schedules available for riders at the front of the bus. He doesn’t seem to go anywhere, or be headed anywhere, just riding around in traffic.

STOP.

I get off the bus back at the Clermont Park & Ride. There are 8 cars in the parking lot. 2 belong to the county. I walk the 9 bus lengths to my car, then drive the 5 miles or 11 minutes back to my driveway.

—

* The length of the campground is .3 miles, or 1,584’. A New York City block is 264’ wide.

** Her unique schedule could identity her. She works at Walmart and somewhere else.

—

An excerpt from this essay appears in USF’s Saw Palm Florida Literature & Art “Places to Stand” series.